Rossbeigh Area Walks

LOCATION: Rossbeigh, Glenbeigh

LENGTH: 2km to 10km

DIFFICULTY: Easy to Moderate

PARKING: Faha Wood OR Rossbeigh

A little bit about the area

Our map does not correspond to exact points or numbered signs along the trail. Instead, this map is seen as a companion for the area, filling you with information on what you might find and where you might find it. It will hopefully add to your enjoyment of this wonderful corner of Iveragh and help build the memories that will stay with you long after you leave.

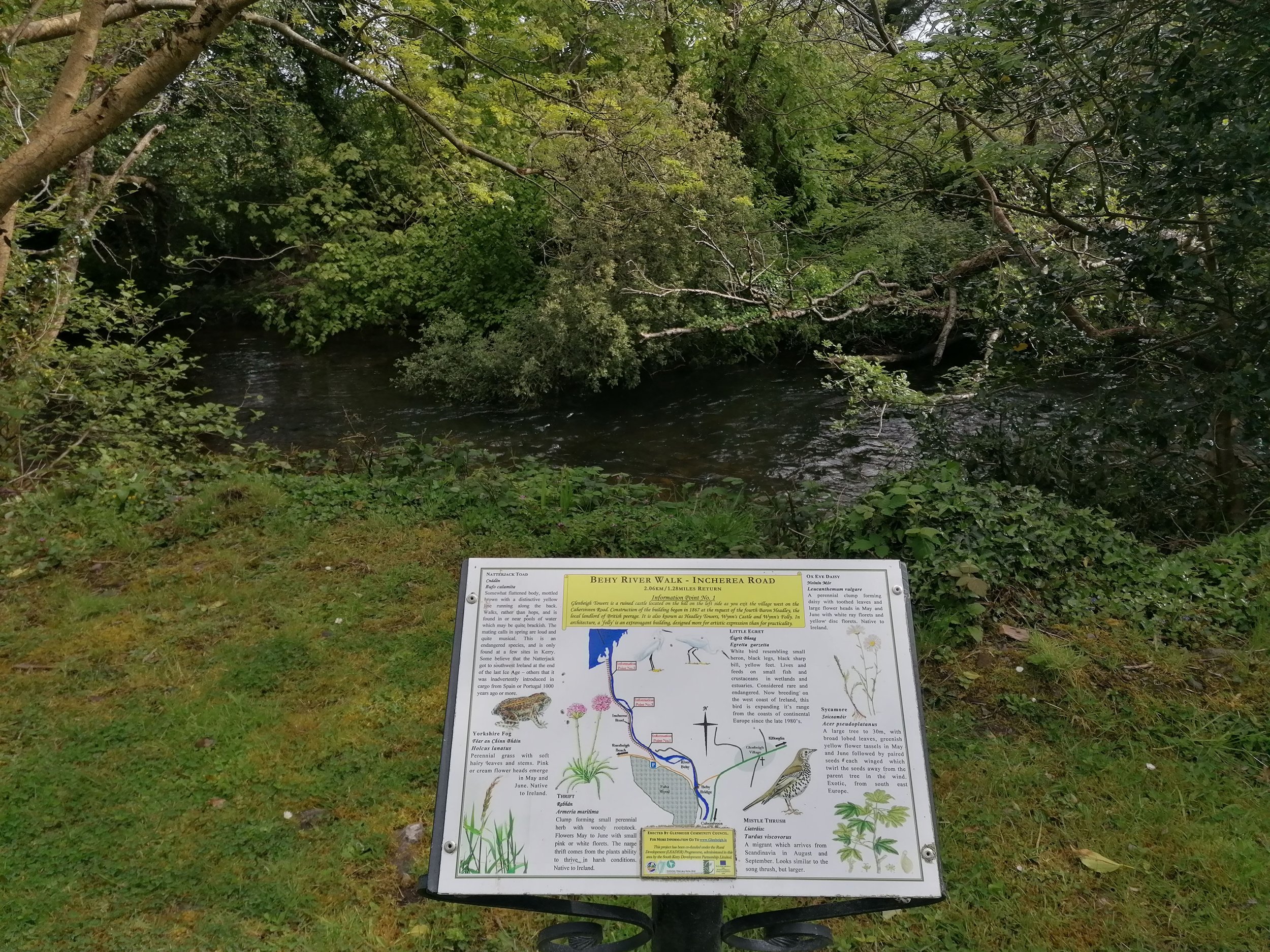

The black line follows the road from Glenbeigh village west to Rossbeigh. Much of this narrow road lacks footpaths, so please take care if walking this route. From its start point at the Behy Bridge, the purple route follows the Behy River Walks along ‘Cois na hAbhainn’ via the Behy Grove Road, and along the Incherea Road, which brings you from Faha Wood to a viewpoint overlooking Castlemaine Harbour. This second route follows the Behy River along a residential road and is accessible to wheelchair users and children's strollers - except for the last section, which enters the harbour lookout point via uneven ground.

Faha Wood Fairy Forest is marked in green and is a steep, uneven woodland trail sprinkled with fairy homes in a conifer wood. The blue route is the rough, and sometimes steep, Glenbeigh to Rossbeigh trail which is best travelled from east to west to take in the spectacular views of the sand spit. Finally, in grey is the Rossbeigh Beach Loop which is best completed at low tide. Click on the points on the map below to learn about what you might see or hear while exploring - along with some snippets of local history.

Dogs are not permitted on the section of the trail from Faha Wood to Rossbeigh due to the presence of farm animals. We respectfully ask that dogs are kept on leads in all other areas, especially in the sensitive wetland bird habitats, thank you. Have a look at Glenbeigh.ie for more information on your stay in the area.

HOW TO EXPERIENCE THE MAPS:

The map locations can be seen on your mobile device. Clicking on the square icon in the top right hand corner of the respective map to open the map in a web browser or Google maps app. Or you can click on the square in the top left of the map to follow it on this page.

TRAIL GUIDE:

Below the maps is the guide for the map and the selected points.

There is also an alternative Storymap:

Rossbeigh Area Walks Guide

1. Rossbeigh Beach Entrance

Rossbeigh Strand stretches for nearly 3km out into Dingle Bay and is a wonderful place to stretch the legs and let the mind wander. At low tide, it is possible to walk the length of the sand spit and follow a loop to return on the opposite side. If you fancy something a little different, you could always explore some of the area on horseback with the local horse-riding centre. For those who are less mobile, a number of accessible parking spaces are available at this map point, which is the main entrance to the sand spit. From here, you will feel the fresh sea-breeze and hear the sounds of waves crashing along the shore. A tarmac path, of 200m in length, leads from this point east along the roadway back towards Glenbeigh and is a great spot to look for winter wading birds. You might hear the bubbling call of the Curlew (Crotach or Cuirliún) on the wind or see Brent Geese (Cadhan) feed in the lagoon at hightide.

This area is a handy base for exploring Rossbeigh. Plenty of parking is available, although it should be noted that it is mostly on uneven ground and boulders from the seawall are often moved around here during winter storms. The playground is a wonderful amenity for the little ones, while the tennis court offers a seaside challenge for the more energetic. Public toilets are also available, and those who work up an appetite have options at the entrance to the strand or back in Glenbeigh. Iveragh has many beaches that offer memorable experiences all year round; can find out more in our ‘Winter on Iveragh’ section.

2. Pebble Beach

Across the sand spit at Rossbeigh, large pebble-sized material has accumulated. This is a storm beach which forms as this large material is deposited by high-energy waves during storm events. These pebbles vary in size and composition but are overwhelmingly sandstone and siltstones of the Old Red Sandstone. These Old Red Sandstones are predominantly purple, green and grey in colour.

As these are sedimentary rocks, they were deposited in rhythmic layers as the sediments accumulated over time, with each layer representing a period of geological time. These fine layers are known as laminations (1st image) and are formed by changes in sediment supply. When these layers are very regular, and of similar size, it suggests that the sediments were deposited by cyclic events, such as during seasonal flooding.

Bands of white are found across many of the pebbles along the beach. These are Quartz veins (2nd image), which formed as hot fluids carrying dissolved minerals from deep within the earth seeped into small fractures and cracks. As the fluid cooled, the minerals gradually precipitated, leaving these distinct white bands across the rocks. White pebbles of quartz are also found along the beach.

Jasper is immediately distinguishable due to its distinct deep red colour (3rd image). Jasper is an impure variety of silica which often forms from the aggregation of sand grains. The red colour of jasper is due to the presence of iron.

Black Shales are very fine-grained sedimentary rocks which are composed of clay, quartz, silt and organic particles (4th image). The black or dark colour of these rocks suggest that they contain abundant organic matter. These rocks were deposited in marine conditions.

-

3. What's in a name?

Rossbeigh, Glenbeigh, Behy River... you must be wondering what these names mean. Ros is the Irish for a hill or promontory that is usually wooded; Gleann refers to a glen or valley; Beithe refers to birch trees. When you put these together, you can imagine the scene around this area when early settlers decided upon these names. A valley with birch woods that also possibly lined the sides of the Behy (Birch) River. Understanding the origin of Irish place names often gives more meaning to a location and may reveal a landscape much different to the present day. Logainm.ie is a great website to explore Irish place names and their meanings.

-

4. Red-billed Chough

The first thing that might draw your attention to this member of the crow family is their 'keee-aawww' call. The Red-billed Chough is known as a 'Cág Cosdearg' in Irish, which translates as 'red-legged jackdaw' which offers a clue as to their appearance. As well as having red legs, the chough also has a long, curved, red bill which is uses to probe the ground for food. This is a rare species that is only found along Ireland’s Atlantic coastline. The cliffs of Iveragh are home to nesting choughs and they can be seen - and heard - over the dunes and wetlands of Rossbeigh.

-

5. The Sunbeam

In 1903, a wooden schooner named the Sunbeam ran aground off Rossbeigh. A storm pushed the Sunbeam onshore as she was travelling with flour from Kinvara to Cork, but thankfully no lives were lost. The ship lay on the strand beneath the waves for decades and gradually its skeletal hull became all that was visible, partially buried by the sands and covered by high tides. A photographer’s dream, a quick search of ‘Sunbeam Rossbeigh’ will fill your screen with images taken by many over the years. 2014 brought a winter of heavy storms to Iveragh and it was Storm Darwin that bore down on Rossbeigh the hardest. The aftermath revealed huge damage to the beachfront – boulders moved, roads uplifted, playground destroyed, and creatures of the seabed thrown onto the beach. The strength of Darwin also lifted the Sunbeam from its sandy grave and pushed it against the base of the sand dunes. Visitors flocked to see the ghostly ship - risen after over 100 years buried. Storm after storm, winter after winter, tide after tide, the Sunbeam’s remains shifted with time and its movements are now monitored by the CHERISH Project.

6. Mountains

One of the most striking aspects of the physical landscape of the Glenbeigh area is the mountains that stretch along the coastline. At the end of the Carboniferous Period, the Iveragh Peninsula got caught up in a mountain building event which had a profound impact on the landscape. As continental plates collided, intense pressure squeezed and compressed the previously flat layers of rock and piled them up to form vast mountain chains. This mountain building event is known as the Variscan Orogeny and lasted from around 318 to 290 million years ago. It was during this event that the east-west oriented fold mountains of the MacGillycuddy’s Reeks were formed and the overall ridge and valley landscape of Iveragh was created.

Following this mountain building event, there is a large gap in the geological record. Evidence from other areas shows that during this period, Ireland was alternately submerged beneath shallow seas and covered by hot deserts. The next phase of Iveragh’s geological history comes from the Ice Ages of the Quaternary.

-

7. Sand Dunes

Sand dunes are special habitats that are home to unique flora and fauna. Marram grass binds together the sand it captures, which helps in the building of dune structures. The grass holds nutrients and freshwater which, in turn, creates the right environment for flowers such as Orchids (Magairlín). Salt-tolerant plants such as Rock Samphire (Craobhraic) and Thrift (Rabhán) are a few of the many species that can be found in these areas. Visit our 'End of Summer - a Plant's Life' article to help you ID some of those you may find here in Rossbeigh. Dune habitats are very sensitive to erosion, so please be mindful of this and stick to the main trails.

-

8. Rossbeigh Tower

A tower stood at the tip of Rossbeigh sand spit for over 150 years, marking the safe passage route through to Castlemaine Harbour. In February 2010, after gradual erosion over the years, the tower finally succumbed to the power of the Atlantic. While the tower is gone, its memory lives on in the form of a replica which can be seen on arrival into Glenbeigh, from the Killorglin side. Built by local volunteers from the ruins of the original tower, this monument is a beautiful reminder of the history of the strong connection between the sea and Iveragh's coastal communities. You can see images of the original Rossbeigh Tower by Iveragh-based photographer Michael Herrmann here.

-

9. Castlemaine Harbour

Castlemaine Harbour is the area protected from the brunt of the Atlantic Ocean by the Rossbeigh and Inch sand spits. The area is designated as a ‘Special Protection Area’ and ‘Special Area of Conservation’ due to its critically important habitats and a host of protected bird species that overwinter here. A number of viewpoints such as the end of the Behy River Walk and the back strand at Rossbeigh are wonderful places to visit from Autumn to Spring. Thousands of wetland birds such as Curlew (Crotach), Brent Geese (Cadhan) and Dunlin (Breacóg) arrive each year to feed and shelter – a truly magnificent sight. Enjoy the sounds and maybe even pick up a bird ID book and really get hooked on the ‘Who’s who?’ game. Read some interesting information on these winter visitors and where on Iveragh you might see them in our ‘Winter on Iveragh’ section.

-

10. Glenbeigh Community

Visitors have a selection of walks to choose from in the Glenbeigh area, which is down to the hard work of the Glenbeigh community and the cooperation of landowners. Here, routes are maintained, information signage has been erected and benches have been provided in several areas. These walks are excellent resources for both locals and visitors. Whether you are looking for some exercise, some fresh air to clear your head or to learn something new about what surrounds you, having such a variety of trails is a treat. You can find out more about community news via Glenbeigh.ie or in the wider Iveragh area via the South Kerry Development Partnership. When exploring these areas, it is important to remember to respect that you are passing close to people's homes or crossing their land. We would like to bring to your attention again that we support responsible, sustainable, regenerative tourism.

-

11. Riparian Habitat

The habitat around rivers is known as 'riparian' habitat and it is an ecosystem bursting with life. Everything is connected: the water nourishes trees and plants which feeds the insects. These, in turn, are eaten by fish or birds, which may then be eaten by larger fish, birds, or mammals. Vegetation overhanging the water creates shaded areas in the river, ideal for young fish. Trees and shrubs along the river’s edge not only bind the soil together to prevent erosion, they also filter run-off from the land by capturing sediment that may otherwise choke the flow of the stream or river.

Riverbanks may erode over time due to natural river cycles, but in the meantime, they can be home to Otters (Madra Uisce), Kingfishers (Cruidín) or Sand Martins (Gabhlán Gainimh). Insects, such as some mining bee species, will collect mud from riverbanks to build their homes elsewhere. The wetlands attached to rivers are also a great place to look for Dragonflies (Snáthaid Mhó). The National Biodiversity Data Centre have some wonderful swatches to help you ID a host of Irish flora and fauna. Flood plains surrounding rivers are also a vital protection to the environment during high rainfall. These areas often contain species specially adapted to floods, such as Willow (Saileach), Alder (Fearnóg), or the Birch (Beithe) tree which appears so frequently in the region’s placenames.

-

12. River Life

It’s such a pleasure to sit by a stream. To relax to the sound of flowing water and tune in to the birdsong in the surrounding habitat. There is a certain cast of characters that are more likely to be found by running water – Kingfishers (Cruidín), Dippers (Gabha Dubh), Grey Wagtail (Glasóg Liath), Spotted Flycatchers (Cuilire Liath), Heron (Corr Réisc) and Little Egret (Éigrit Bheag) are just a few. These birds specialise in preying on the insects in and around flowing waters or the fish which inhabit them. You may be lucky enough to spot an Otter (Madra Uisce), either plodding along the bank or perhaps a brief glimpse of their whiskered face peering from the water. Many animals come to streams and rivers to drink so it’s always worth checking sandy or muddy areas for tell-tale tracks and a game of ‘Who’s who?’.

-

13. Freshwater Life – Fish

Fish in our freshwater bodies come in all shapes and sizes, from Minnows (Bodairlín) to Salmon (Bradán), and most of us will only ever experience a brief glimpse of them from the water’s edge. Perhaps a flash of silvery scales or a shadowy dart for cover. I’ve often stood on a bridge watching Trout (Breac) parr from above, mesmerised by the constant effort to steady themselves into the flow of water. Some fish are what we call anadromous, meaning that they can spend much of their lives in freshwater before making certain biological adjustments to survive in saltwater. Salmon and sea trout are examples of such fish. It’s not just the bigger fish that have interesting lives, the humble Stickleback (Garmachán) is just as engaging. The males flap their bodies horizontally to create hollows in the riverbed and arrange pebbles and vegetation with their mouths. They build a tunnel shaped ‘nest’ glued together with a sticky substance they secrete from their kidneys. Females lay their eggs in the most impressive nests and males guard these eggs until they hatch – frequently fanning them with his tail to ensure they have enough oxygen to grow. Amazing! A handy ID guide for Irish freshwater fish can be found here.

-

14. Freshwater Life – Invertebrates

Freshwater bodies such as streams, rivers, bogs and wetlands contain endless life stories including those of the invertebrates. We can readily see the birds and sometimes the fish too, but what are they eating? Many species of flying insects deposit their larvae in freshwater - where some metamorphose into nymphs - and it’s a hunt or be hunted world. One fascinating example is that of the Cased Caddisfly (Cruimh Chadáin) larva, which can be seen in this video. The larva glues tiny fragments of wood and sand into the shape of a wearable tube – a DIY suit of armour. The flying adults that we see are often the briefest moments of their lifecycle as many stay in underwater nymph form for the majority of their lives. You can learn more about life in freshwater in this wonderful EPA piece by Hugh Feely.

15. River Processes

Rivers are modern geological agents that mould and shape landscapes. The structure of river landforms depends on a number of factors, including the properties of underlying geological material, the duration the river has been active and the location of the river. Rivers shape the landscape through the erosion, transportation and deposition of materials such as sand, silt and stones.

Rivers have three stages, the upper course, middle course, and lower course, each of which have distinct characteristics and features. The contrast between the upper and lower courses can be clearly seen across the rivers and streams of the Glenbeigh area.

The upper course is characterised by having a steep gradient with erosion dominating over deposition. Features found in the early course of rivers include the river source, tributaries, V-shaped valleys, and waterfalls. Examples of upper stage rivers can be seen along the Faha Wood to Rossbeigh trail. Here, two streams flow down the hillslope where the gradients are steep, and the channels are narrow. As they travelled, the streams have cut downwards and eroded small, steep-walled valleys in the mountain side.

The formation of waterfalls is likely due to the presence of alternating bands of rock which were overturned during the Variscan Orogeny. Although these bands all belong to the Old Red Sandstone formation, slight variations in composition mean that some layers are softer than others. The softer rocks are more prone to erosion, so the waterfall forms when water falls onto these softer layers.

The middle course is characterised by having a gentle gradient with both erosion and deposition occurring. Features found in the middle course of rivers include meanders, slip-off slopes, and river cliffs. The area around the Behy Bridge shows a river at its middle course. At this point the gradient is very gentle and the river is wide with large meanders. However, the river still flows quite fast at this point, meaning that erosion is still occurring.

-

16. Behy River - Cois na hAbhainn Road

The bridge at the start of the Behy River walks is a perfect spot to look for a Dipper (Gabha Dubh). Dippers are a truly wonderful bird to watch. Their unmistakable white bib on a dark brown body, which bobs up and down almost continuously, makes them difficult to confuse with any other bird. They will often perch on a mid-stream stone before plunging into the flow. Watch as the water beads simply roll off their waterproof feathers as they appear to ‘plough’ their way through the shallow water, poking and prying under stones for food. They are capable of diving into deeper pools too and will often re-emerge with a shelled food item which is unceremoniously swung at a rock until the soft contents are revealed and devoured. If you look closely, you may notice that their eyelids are covered in fine white feathers. Flowing water can be a noisy habitat and one theory is that flashing these white eyelids when blinking helps when communicating with other dippers, in conjunction with calls and song.

-

17. The Kerry Way

The Kerry Way is a 214km walking route taking in many of the upland and coastal trails that loop around the Iveragh Peninsula. Taking up to 10 days to complete the full loop, the trail can be broken down into individual sections that followed old market routes and mass paths. With the generous co-operation of landowners, many stunning corners of the peninsula have been turned into hiking trails by the South Kerry development Partnership; you can find more information here. A section of this trail passes through Glenbeigh, so the town is a lovely spot to take a break from walking and relax by the sea.

-

18. Faha Wood Car Park

A small parking area is located here, ideal for the Behy River Walk, Faha Woods or Glenbeigh to Rossbeigh walks. No toilet facilities are available.

-

19. Faha Wood Fairy Forest

Everyone knows how difficult it is to spot a fairy. A quick flash of colour out of the corner of your eye or a distant hint of music on the breeze through the trees might be the closest you'll get. If there is one place where your chances are a little higher it has to be Faha Wood. With population of fairies believed to be the largest in Ireland, this woodland trail has everything a fairy could need: woodland birds to sing them a song, views of Rossbeigh and a variety of trees to provide them shelter. Don't forget to look and listen carefully for the birds in the woods too; a bit like fairies, they are shy and sing beautiful songs for you to listen to. You can learn some common bird songs here.

-

20. Fabulous Fungi

In Faha Wood Fairy Forest and other woods around the world, a very important part of the ecosystem are fungi, or mushrooms. They have an important job of breaking up fallen trees, branches or leaves into smaller pieces to be absorbed back into nature. This is why you often find them on old, rotting wood. Fungi come in all shapes and sizes, so next time you are fairy spotting, see if you can find different colour or shapes of fungi. You don't need to touch them, just leave them where they are, as fungi are very important to fairies. On a wet day you might find a fairy or two taking shelter under an umbrella-like fungi or having a snooze on top of a pillow-like fungi. Grown-ups can enjoy this mushroom spotting game too; visit our sections on ‘Fungi – a Kingdom unto themselves’ and ‘Winter on Iveragh’ for more information.

-

21. Geological History

The area around Glenbeigh and Rossbeigh is underlain by two distinct rock formations. The hills and mountainous regions to the south are composed of Devonian Old Red Sandstone, while the rocks at the base of Curra Hill are composed of Carboniferous limestones and shales.

The Devonian Old Red Sandstones in the area were deposited from around 385 to 360 million years ago. These rocks consist of many layers of sandstones, siltstones, slates and conglomerates which are generally red, purple, grey and green. During this time Ireland was located just south of the equator and the area was much hotter than it is today. The sediments which form these rocks were carried down from high mountainous regions in the north by river channels and floods and deposited within an extensive floodplain that extended from Kerry in the west to the Commeragh Mountains in Waterford to the east. The Old Red Sandstones are by far the most common rock in the area, covering almost all of the Iveragh Peninsula.

Towards the end of the Devonian, the coastline was gradually moving northwards across this floodplain and by the Carboniferous period, around 359 million years ago, the area was covered in warm, shallow seas. These seas hosted abundant marine life including corals, brachiopods, crinoids and fish. The rocks deposited within this environment were predominantly limestones with some sandstones, mudstones and shales. These were generally deposited in flat, horizontal layers on the shallow sea floor.

22. Quaternary Ice-Ages

By the Quaternary, our present geological period which began 2.6 million years ago, Ireland had completed its northward drift and obtained its present geographic position. Around 2.6 million years ago the global climate began to oscillate between climatically warmer periods and periods of extreme cold. The glacial deposits and features of the Iveragh Peninsula mostly come from the Last Glacial Maximum, which began around 25,000 years ago.

At the time much of southwest Ireland was occupied by an ice body, known as the Kerry-Cork-Ice-Cap, which radiated outwards from an ice dispersal centre near the source of Kenmare River. The dominant direction of ice movement across Iveragh would have been westwards, towards the Atlantic. As it moved across the peninsula this ice body was fed by a number of smaller glaciers which formed in the mountains and flowed down to the lowlands. In the area around Glenbeigh there was also a significant component of northwards flow as ice breached the mountains and flowed into Dingle Bay.

As glaciers move across the land, they collect large amounts of debris, rocks and dirt that fall onto the surface of the glacier, are picked up from the underlying earth surface, or are pushed and bulldozed by the glacier as it advances. As the ice retreated and melted at the end of the Ice Age, these sediments were dumped and left behind as sheets of unsorted mud, sand, clay, pebbles, and boulders. Deposits of this sediment, known as glacial till are found around Glenbeigh. These till deposits (1st image) are best seen along the northern coast of Iveragh where they form coastal cliffs.

As the ice began to melt and retreat at the end of the Ice Age vast amounts of debris-rich meltwater were produced. This meltwater commonly drained through the low-lying regions between mountains, where it eroded deep meltwater channels. Significant remnants of these meltwater channels are found on either side of Knockboy and Drung Hill.

Throughout the Quaternary, periglacial conditions have also existed in Ireland on numerous occasions. In fact, tundra conditions were prevalent in the period following the last glaciation which ended around 14,000 years ago. In these cold, near-glacial areas, intense freeze-thaw activity produced unique periglacial features and landforms. Across the Glenbeigh area, a type of periglacial feature known as patterned ground is found. These often take the form of polygons. These formed as ice lenses grown in the soil and the constant expansion and thawing make the ground uneven through frost heave. The ice pushes material to the surface and the coarser stones roll down the side of the uneven ground while the finer material stays in the middle.